Object-Oriented Programming: Classes#

In this episode we will take a look at Object-Oriented Programming (OOP) in Python! Object-oriented programming is a powerful paradigm that allows you to structure your code in a way that reflects the real-world entities and their interactions. In Python, OOP is a fundamental aspect of the language, providing a robust and flexible approach to designing and organizing code.

However before we will start learning OOP I want to cover some aspects of Namespaces and Scopes in Python.

Namespace and Scopes#

Namespace#

Earlier in our discussions about variables in Python, we established that a variable essentially acts as a link to an object in the computer’s memory. Visualizing this relationship, we can group variables and their corresponding objects into pairs, creating a structured mapping.

namespace = {"obj1": obj1, "obj2": obj2, ...}

This simply is a namespace in Python. So in Python, namespace act as dynamic containers, responsible for establishing a mapping between names and objects. Think of a namespace as an intelligent dictionary, where names are keys, and objects are values. This dynamic mapping allows Python to efficiently manage and organize the various elements within your program. For next code snippet:

# Variable "x" pointing to an object in memory

x = [1, 2, 3]

we could say that namespace mapping is {"x": [1, 2, 3]}.

In Python, we like to keep things organized. So, the print function and our variable x don’t share the same space.

Why? Well, Python has different areas, called “scopes”, and each of them has its own place to store names and their stuff.

It’s like having separate rooms for different things. Now, let’s explore these scopes in Python.

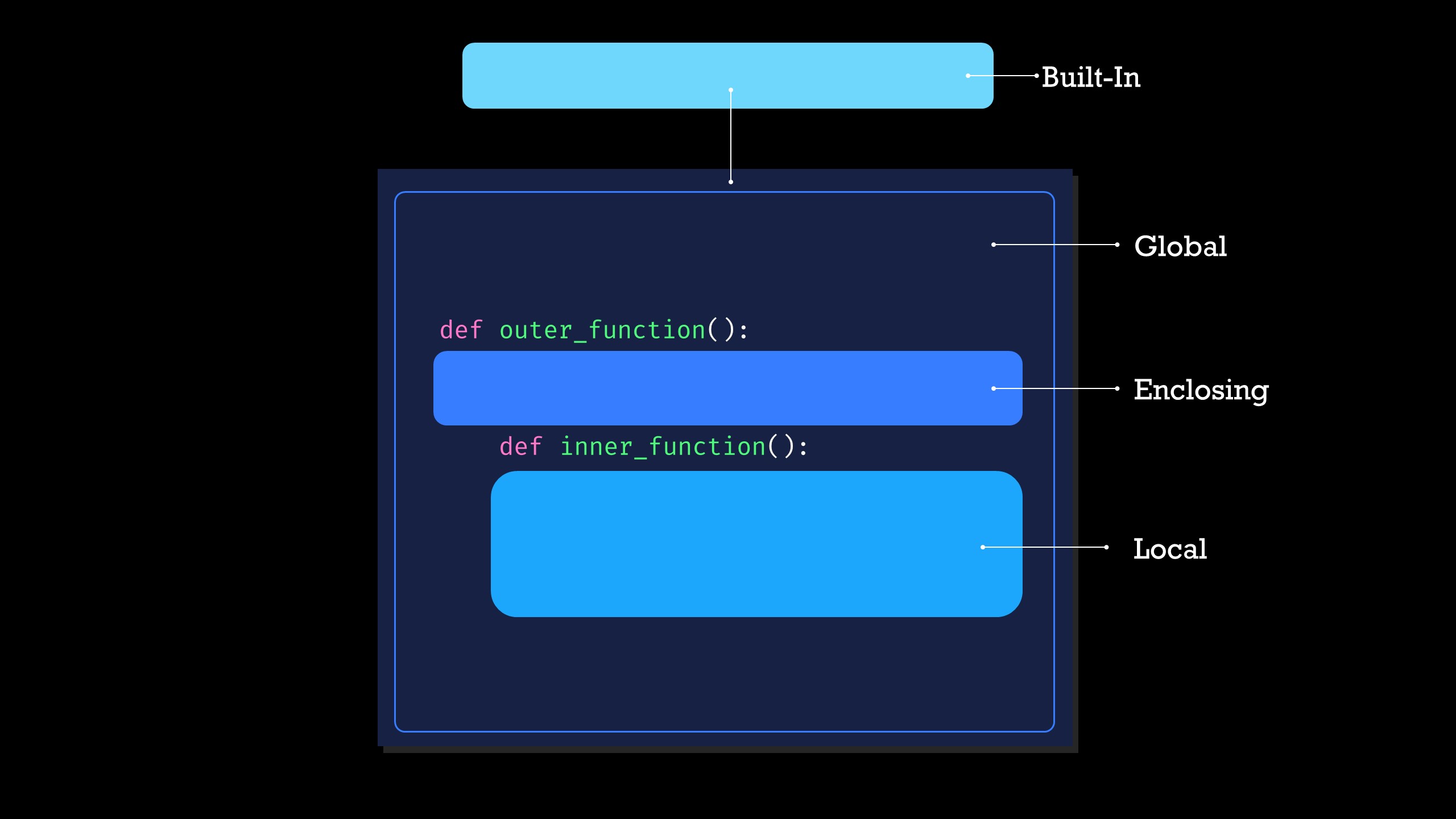

Scopes#

Local scope#

Local scope refers to the part of your code, usually within a function or method, where variables have local significance. Each function call creates its own local namespace.

When a function is called, a local namespace is created, acting as a container for variables within that function. This namespace is isolated from the global namespace.

def local_scope_example():

local_variable = "I am local"

print(local_variable)

local_scope_example()

# This line would raise an error as local_variable is not accessible here.

# print(local_variable)

I am local

Enclosing scope#

Enclosed scope. This scope occur when functions are defined within other functions. Each function has its own local namespace, and it can access variables from its own namespace as well as those from the enclosing scopes.

In the example below, inner_function has access to both its local namespace and the namespace of outer_function.

def outer_function():

outer_variable = "I am in the outer function"

def inner_function():

inner_variable = "I am in the inner function"

print(outer_variable)

print(inner_variable)

inner_function()

outer_function()

I am in the outer function

I am in the inner function

Global scope#

Global scope encompasses the entire Python script or module. Variables in the global scope are accessible from any part of the code.

Variables defined outside any function or method belong to the global namespace. They persist throughout the program.

global_variable = "I am global"

def global_scope_example():

print(global_variable)

global_scope_example()

print(global_variable)

I am global

I am global

Built-in scope#

The built-in scope is encompassing all reserved keywords. They can be readily accessed anywhere in the program without requiring explicit definition before usage.

For example built-in scope contain such names as print, len, sum, etc.

LEGB Rule and Namespace Search Order#

The LEGB rule (Local, Enclosing, Global, Built-in) determines the order in which Python searches for a variable.

When a variable is referenced, Python searches for it in the following order:

Local (L): Inside the current function’s local namespace.

Enclosing (E): In the local scopes of any enclosing functions (for nested functions).

Global (G): In the global namespace.

Built-in (B): In the built-in namespace where Python’s predefined names reside.

Note

When I think about namespaces and scopes, I picture it like looking for things in different rooms. Imagine your current room as your “local scope.” If you’re trying to find something (an object), you’d check your current room first. If it’s not there, you might check another room nearby (enclosing room), and so on. It’s like a step-by-step search through rooms until you find what you’re looking for!

Interaction with namespaces#

You can check namespaces using the globals(), locals() and dir() functions.

Let’s explore each of them.

globals() function returns a dictionary representing the global namespace.

When called within a function or at the module level, it provides access to the global namespace, allowing you to inspect or modify global variables.

global_variable = "I am global"

def check_globals():

print(globals())

check_globals()

Show code cell output

{'__name__': '__main__', '__doc__': 'Automatically created module for IPython interactive environment', '__package__': None, '__loader__': None, '__spec__': None, '__builtin__': <module 'builtins' (built-in)>, '__builtins__': <module 'builtins' (built-in)>, '_ih': ['', 'def local_scope_example():\n local_variable = "I am local"\n print(local_variable)\n\nlocal_scope_example()\n# This line would raise an error as local_variable is not accessible here.\n# print(local_variable)', 'def outer_function():\n outer_variable = "I am in the outer function"\n\n def inner_function():\n inner_variable = "I am in the inner function"\n print(outer_variable)\n print(inner_variable)\n\n inner_function()\n\nouter_function()', 'global_variable = "I am global"\n\ndef global_scope_example():\n print(global_variable)\n\nglobal_scope_example()\nprint(global_variable)', 'global_variable = "I am global"\n\ndef check_globals():\n print(globals())\n\ncheck_globals()'], '_oh': {}, '_dh': [PosixPath('/home/vdsukhov/gitrepos/github/python-intro-course/chapters')], 'In': ['', 'def local_scope_example():\n local_variable = "I am local"\n print(local_variable)\n\nlocal_scope_example()\n# This line would raise an error as local_variable is not accessible here.\n# print(local_variable)', 'def outer_function():\n outer_variable = "I am in the outer function"\n\n def inner_function():\n inner_variable = "I am in the inner function"\n print(outer_variable)\n print(inner_variable)\n\n inner_function()\n\nouter_function()', 'global_variable = "I am global"\n\ndef global_scope_example():\n print(global_variable)\n\nglobal_scope_example()\nprint(global_variable)', 'global_variable = "I am global"\n\ndef check_globals():\n print(globals())\n\ncheck_globals()'], 'Out': {}, 'get_ipython': <bound method InteractiveShell.get_ipython of <ipykernel.zmqshell.ZMQInteractiveShell object at 0x7f1ef043fd70>>, 'exit': <IPython.core.autocall.ZMQExitAutocall object at 0x7f1ef0102210>, 'quit': <IPython.core.autocall.ZMQExitAutocall object at 0x7f1ef0102210>, 'open': <function open at 0x7f1ef59c0180>, '_': '', '__': '', '___': '', 'platform': <module 'platform' from '/home/vdsukhov/mambaforge/envs/jb/lib/python3.12/platform.py'>, 'sys': <module 'sys' (built-in)>, 'readline': <module 'readline' from '/home/vdsukhov/mambaforge/envs/jb/lib/python3.12/lib-dynload/readline.cpython-312-x86_64-linux-gnu.so'>, 'original_ps1': '>>> ', 'is_wsl': True, 'REPLHooks': <class '__main__.REPLHooks'>, 'get_last_command': <function get_last_command at 0x7f1ef0115da0>, 'PS1': <class '__main__.PS1'>, '_i': 'global_variable = "I am global"\n\ndef global_scope_example():\n print(global_variable)\n\nglobal_scope_example()\nprint(global_variable)', '_ii': 'def outer_function():\n outer_variable = "I am in the outer function"\n\n def inner_function():\n inner_variable = "I am in the inner function"\n print(outer_variable)\n print(inner_variable)\n\n inner_function()\n\nouter_function()', '_iii': 'def local_scope_example():\n local_variable = "I am local"\n print(local_variable)\n\nlocal_scope_example()\n# This line would raise an error as local_variable is not accessible here.\n# print(local_variable)', '_i1': 'def local_scope_example():\n local_variable = "I am local"\n print(local_variable)\n\nlocal_scope_example()\n# This line would raise an error as local_variable is not accessible here.\n# print(local_variable)', 'local_scope_example': <function local_scope_example at 0x7f1ef0116b60>, '_i2': 'def outer_function():\n outer_variable = "I am in the outer function"\n\n def inner_function():\n inner_variable = "I am in the inner function"\n print(outer_variable)\n print(inner_variable)\n\n inner_function()\n\nouter_function()', 'outer_function': <function outer_function at 0x7f1ef0116700>, '_i3': 'global_variable = "I am global"\n\ndef global_scope_example():\n print(global_variable)\n\nglobal_scope_example()\nprint(global_variable)', 'global_variable': 'I am global', 'global_scope_example': <function global_scope_example at 0x7f1ef0116f20>, '_i4': 'global_variable = "I am global"\n\ndef check_globals():\n print(globals())\n\ncheck_globals()', 'check_globals': <function check_globals at 0x7f1ef0116d40>}

locals() returns a dictionary representing the local namepsace.

When called within a function, it provides access to the local namespace of that function, allowing you to inspect or modify local variables.

def check_locals():

local_variable = "I am local"

print(locals())

check_locals()

Show code cell output

{'local_variable': 'I am local'}

dir function returns a list of names in the current scope or a list of attributes of an object if an object is provided.

It’s a versatile function. When used without arguments, it shows the names in the current scope. When used with an object as an argument, it lists the attributes of that object.

print(dir())

Classes#

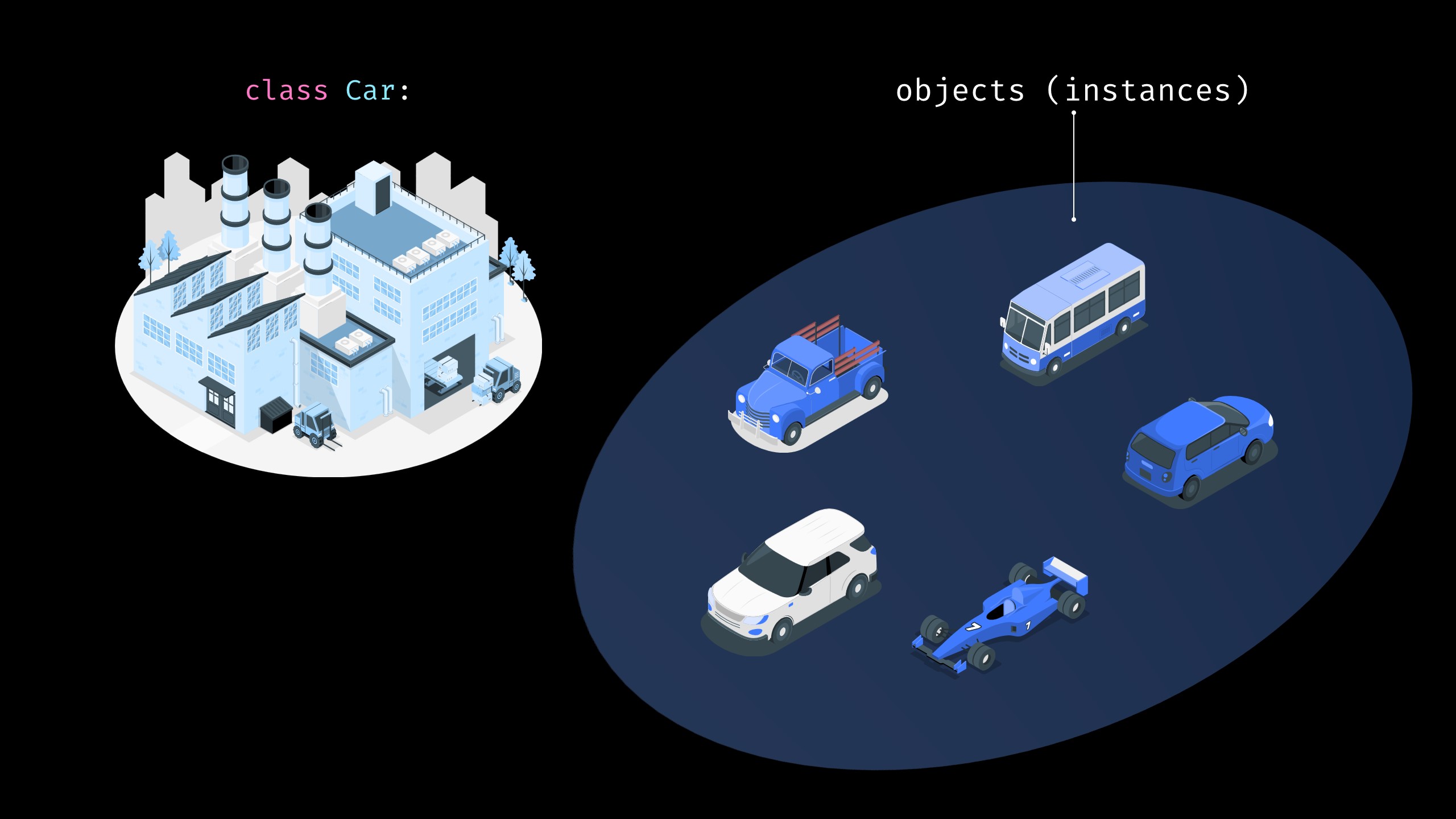

Let’s create a simple class for a Car in Python. A class is a blueprint for creating objects, and it encapsulates both data (attributes) and behavior (methods) related to the object. In this case, we’ll define a Car class with some basic attributes and methods.

We will use the following attributes to describe our class:

brand- simply car brandmodel- the modelyear- the year when car was assembledcolor- color of the carfuel- the current fuel levelodometer- the distance traveled by a vehicledoors_locked- current doors status (i.e. locked or unloced)

class Car:

def __init__(self, brand, model, year, color, fuel=100, odometer=0, doors_locked=True):

self.brand = brand

self.model = model

self.year = year

self.color = color

self.fuel = fuel

self.odometer = odometer

self.doors_locked = doors_locked

Here we defined our blueprint for objects using the class keyword.

Think of a class as a template that outlines the structure and behavior of our objects.

Inside our class, we currently have one special method called __init__.

This method is like a constructor and is used to create new instances (objects) of our class. It initializes the attributes of the object when it is first created.

Now, let’s put our class to use by creating a couple of objects. These objects will be unique instances of the Car class, each with its own set of attributes.

camry = Car(brand="Toyota", model="Camry", year=2023, color="red")

tesla_x = Car(brand="Tesla", model="X", year=2023, color="black")

After specifying our objects, we can access their attributes by using a dot after the variable name and specifying the attribute name:

print("camry fuel level:", camry.fuel)

Show code cell output

camry fuel level: 100

__init__ method#

In Python, when we create a class, we use a special method called __init__ to set up the initial state of the object.

This method is like a guidebook for creating new objects based on the class.

Now, here’s the trick: when we define methods inside a class, we need a way to refer to object itslef.

That’s where self comes in!

What is

self?selfis a convention (a tradition, you could say) in Python. It is like a placeholder that refers to the instance of the object that we are working with.

Using

selfWhen we create a new Car, like

camry = Car(brand="Toyota", model="Camry", year=2023, color="red"), Python automatically passescamryas theselfargument to the__init__method. So theself.brand,self.modeland so on, refer specifically to the attributes ofcamry.

Note

You can consider the __init__ method like the birthplace of an object in Python. At the beginning of this method, self is like an empty canvas - an object yet to be fully formed.

As we going through the __init__ method, we are like architects adding features (attributes) to our object one by one.

Class methodes#

So far, we have explored the __init__ method, and you may have observed that this particular method name includes leading and trailing double underscores. In Python, there are several reserved names that, when implemented, allow us to add additional functionality to our class. We will delve into more of these reserved names later in the course. However, we are not limited to using only these reserved methods. We have the flexibility to implement various custom methods of our own. Let’s proceed by adding a couple of custom methods to our class.

class Car:

def __init__(self, brand, model, year, color, fuel=100, odometer=0, doors_locked=True):

self.brand = brand

self.model = model

self.year = year

self.color = color

self.fuel = fuel

self.odometer = odometer

self.doors_locked = doors_locked

def vehicle_status(self):

"""Prints the status of the car including all attributes."""

print(f"Car Status:")

print(f"-- Brand: {self.brand}")

print(f"-- Model: {self.model}")

print(f"-- Year: {self.year}")

print(f"-- Color: {self.color}")

print(f"-- Fuel Level: {self.fuel}%")

print(f"-- Odometer: {self.odometer} miles")

print(f"-- Doors: {'Locked' if self.doors_locked else 'Unlocked'}")

def unlock(self):

"""Unlocks the doors of the car."""

if self.doors_locked:

print("Doors are now unlocked.")

self.doors_locked = False

else:

print("Doors are already unlocked.")

def lock(self):

"""Locks the doors of the car."""

if not self.doors_locked:

print("Doors are now locked.")

self.doors_locked = True

else:

print("Doors are already locked.")

Here we implemented couple methods:

vehicle_statusprints the status of all attributes in a clear formatunlockandlockmethods handle the doors’ locking status

Now let’s call our methods:

camry = Car(brand="Toyota", model="Camry", year=2023, color="red")

camry.vehicle_status()

camry.unlock()

Car Status:

-- Brand: Toyota

-- Model: Camry

-- Year: 2023

-- Color: red

-- Fuel Level: 100%

-- Odometer: 0 miles

-- Doors: Locked

Doors are now unlocked.

We could say that methods are functions that are associated with objects.

They are defined within a class and operate on instances (objects) of that class.

The crucial difference between methods and functions is that methods are linked to specific objects.

When you call a method, often it operates on the particular instance (object) it is associated with.

This connection enables objects to have behaviors tailored to their own state.

For example, a Car object might have a start_engine method that makes sense for cars but might not make sense for other objects.

When you execute a method with an object (object.method()), behind the scenes, it’s like saying Car.method(object). In this context, self refers to the instance of the object you’re working with.

For a quick check, you can run the explicit version by specifying the class name directly. It’s a way of saying, “Hey, this method is designed to work with this specific object.”

Car.vehicle_status(camry)

Car Status:

-- Brand: Toyota

-- Model: Camry

-- Year: 2023

-- Color: red

-- Fuel Level: 100%

-- Odometer: 0 miles

-- Doors: Unlocked

The code above is same as camry.vehicle_status(). The idea is that we can run it directly using the object without always explicitly specifying the class name. As you can see, self corresponds to camry in this specific case.

Class as a factory#

Think of a class as a versatile factory capable of creating (instantiating) objects with distinct features. In the earlier example, our Car class allowed us to model and handle real-world objects — cars complete with their own attributes and behaviors.

In a broader sense, you can create different classes tailored to your specific needs, each with its own set of attributes and methods. For instance, imagine a class designed for working with gene expression data. Here, attributes might include a matrix of counts, while methods could encompass various normalizations and differential expression analysis techniques.

To underscore this concept, consider the popular Python package scanpy designed for the analysis of single-cell data. In scanpy, you encounter specific classes and data types crafted for the nuanced demands of single-cell analysis. These classes seamlessly handle various tasks, showcasing the adaptability and power of object-oriented programming.

Magic methods#

Let’s consider the following setup: we want to add a special attribute to cars that measures their horsepower. Now, let’s say we have a list of different cars and we want to sort them based on their horsepower values. Ideally, we would like to use sorted([car1, car2, car3]) to achieve this.

However, we cannot run this code right away because Python doesn’t know how to compare our car objects. In order to sort our objects, we need to be able to compare them. Currently, if we try to compare our car objects, we will encounter an error.

class Car:

def __init__(self, brand, model, year, color, horsepower, fuel=100, odometer=0, doors_locked=True):

self.brand = brand

self.model = model

self.year = year

self.color = color

self.fuel = fuel

self.odometer = odometer

self.doors_locked = doors_locked

self.horsepower = horsepower

camry = Car(brand="Toyota", model="Camry", year=2023, color="red", horsepower=210)

tesla_x = Car(brand="Tesla", model="X", year=2023, color="black", horsepower=800)

Comparison print(camry < tesla_x) lead us to the following error:

TypeError: '<' not supported between instances of 'Car' and 'Car'

This is where magic methods come to our rescue. Basically, Python has a lot of reserved method names that, when implemented, add new possibilities for our objects.

In this specific case, we want to check whether the left object is less than the right one. To do this, we can implement a method with the name __lt__. Let’s implement it:

class Car:

def __init__(self, brand, model, year, color, horsepower, fuel=100, odometer=0, doors_locked=True):

self.brand = brand

self.model = model

self.year = year

self.color = color

self.fuel = fuel

self.odometer = odometer

self.doors_locked = doors_locked

self.horsepower = horsepower

def __lt__(self, other):

return self.horsepower < other.horsepower

camry = Car(brand="Toyota", model="Camry", year=2023, color="red", horsepower=210)

tesla_x = Car(brand="Tesla", model="X", year=2023, color="black", horsepower=800)

print("Camry has higher power rather Tesla:", tesla_x < camry)

Camry has higher power rather Tesla: False

Now we can sort our objects in ascending order.

nissan_gtr = Car(brand="Nissan", model="GT-R", year=2023, color="black", horsepower=565)

cars = [tesla_x, camry, nissan_gtr]

print(sorted(cars))

[<__main__.Car object at 0x7f1ed3e21760>, <__main__.Car object at 0x7f1ef03a0a70>, <__main__.Car object at 0x7f1ef043ed80>]

As you can see, the sorted method works without any problems.

However, the output doesn’t make a lot of sense to us.

To address this, we can implement another magic method called __repr__.

class Car:

def __init__(self, brand, model, year, color, horsepower, fuel=100, odometer=0, doors_locked=True):

self.brand = brand

self.model = model

self.year = year

self.color = color

self.fuel = fuel

self.odometer = odometer

self.doors_locked = doors_locked

self.horsepower = horsepower

def __lt__(self, other):

return self.horsepower < other.horsepower

def __repr__(self):

return f"Brand: {self.brand}, Model: {self.model}"

camry = Car(brand="Toyota", model="Camry", year=2023, color="red", horsepower=210)

tesla_x = Car(brand="Tesla", model="X", year=2023, color="black", horsepower=800)

nissan_gtr = Car(brand="Nissan", model="GT-R", year=2023, color="black", horsepower=565)

cars = [tesla_x, camry, nissan_gtr]

print(*sorted(cars), sep='\n')

Brand: Toyota, Model: Camry

Brand: Nissan, Model: GT-R

Brand: Tesla, Model: X